Wildlife Connections: Habitat Trees

By Josie Miller

Urban trees are valued for the ecosystem services that they provide, such as energy conservation, carbon sequestration, air quality enhancement, and stormwater mitigation. Additionally, urban trees are valued for the social services they provide, including their effects on the health and wellness of humans. As more people become interested in supporting wildlife, urban trees are increasingly valued for their habitat potential.

What is a wildlife habitat tree?

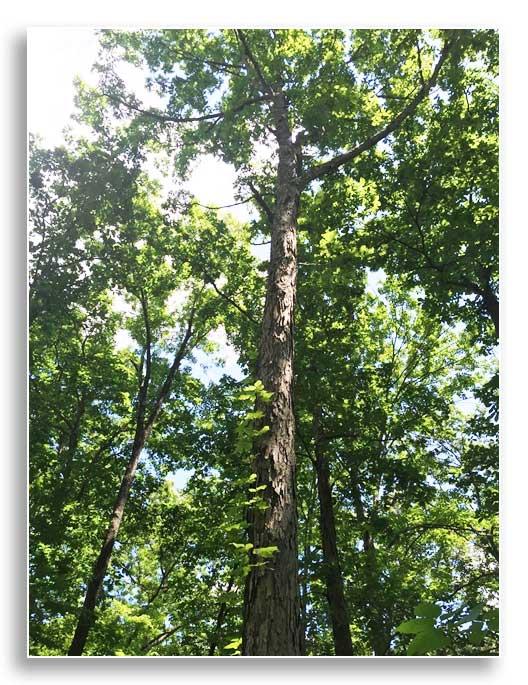

Habitat trees have been defined as “standing live or dead trees providing ecological niches (microhabitats) such as cavities, bark pockets, large dead branches, epiphytes, cracks, sap runs, or trunk rot” (Bütler, R., Lachat, T., Larrieu, L., & Paillet, Y., 2013). These microhabitats are used by a number of animals, plants, and fungi as a place to live, forage, and breed. On living trees, cavities may be formed naturally, such as when a large branch breaks and the exposed wood begins to rot, or they may be excavated by primary cavity nesters such as pileated woodpeckers or northern flickers. Bark pockets may be associated with a particular tree species, such as shagbark hickory that has naturally peeling bark, or they may occur on a dead tree on which the bark has begun to slough off as part of the decay process. Overall, standing dead trees, also known as snags, and dying trees are thought to benefit hundreds of species.

Habitat tree residents

Urban residents of habitat trees include birds, small mammals, amphibians and reptiles, arachnids, and insects. Each of these animals finds shelter from predators and weather in the insulated nooks of a habitat tree. Additionally, plants, lichens, and fungi may use a tree as a growing substrate or food source. Birds may use dead branches on the tree as a perch from which to sing or hunt, or use a cavity as a place to roost or nest. Secondary cavity-nesters, such as bluebirds and flying squirrels use natural cavities, or the vacant cavities previously excavated by woodpeckers (primary cavity-nesters.) Birds, such as brown creepers, and bats may also inhabit the protected spaces behind loose or sloughing bark. Amphibians and reptiles take advantage of cracks as both a safe hiding place and hunting grounds for insects. All of these animal residents add to the ecological function of the urban forest. By welcoming birds, bats, and other insectivores, humans and trees alike benefit from the resulting insect pest control.

Incorporating wildlife trees into an urban setting

Although habitat trees are common in unmanaged forests, they are lacking in the urban environment. Due to safety and aesthetic concerns, habitat trees are often removed from these settings. In order to encourage urban wildlife, more people are choosing to keep, or even create wildlife trees. Maintaining an urban wildlife tree requires a commitment to manage the tree, but rewards the manager with myriad opportunities for wildlife viewing.

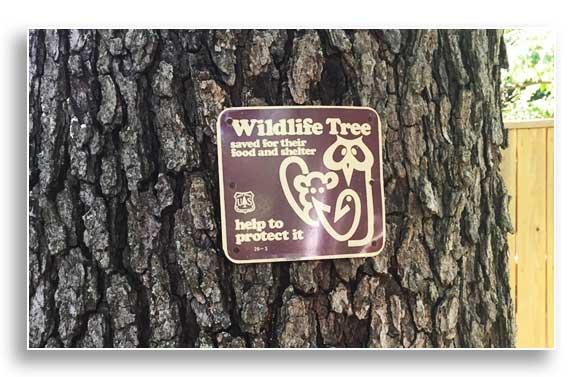

Because wildlife trees may be potentially hazardous, it is important to consult an ISA Tree Risk Assessment Qualified Arborist when deciding whether or not to keep or create a habitat tree. If a habitat tree is unadvisable for your situation, the arborist may recommend leaving a large stump as an alternative. Cavities and roosting slits may be artificially created by the arborist in order to enhance the stump habitat. Because dead and dying trees are not always recognized as habitat trees, installing signage is an effective way to share your intentions with your community.

Photography

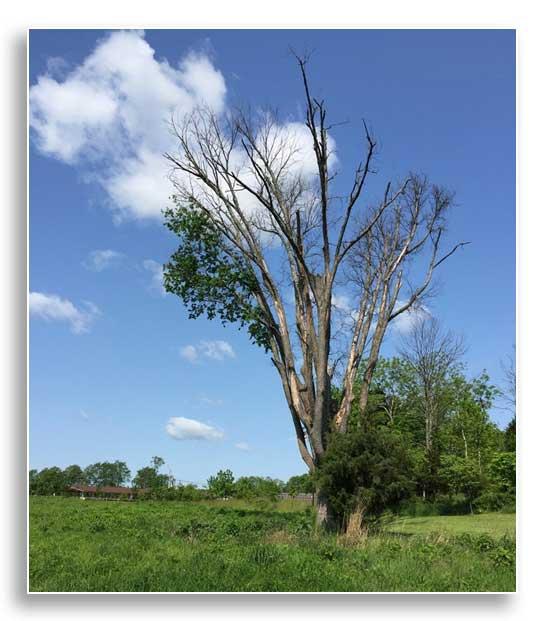

- Declining elm tree (Ulmus americana) in meadow provides habitat for animals with minimal risk to humans. (Josie Miller)

- Shaggy bark of white oak (Quercus alba) behind which bats may hide. (Josie Miller)

- Pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) nestlings in excavated cavity. (“Woodpecker” by Charles de Mille-Isles is licensed under cc by 2.0)

- Black cherry (Prunus serotina) snag protected by homeowner. (Josie Miller)

About the Author

Josie Miller is the Stewardship Director of Floracliff Nature Sanctuary, a 287-acre forest and ecological preserve in the palisades region of the Kentucky River in southern Fayette County, Kentucky. Email @ josiekmiller@gmail.com

Resources

Bütler, R., Lachat, T., Larrieu, L., & Paillet, Y. (2013). Habitat trees: key elements for forest biodiversity. In In Focus—Managing Forest in Europe (2.1). Retrieved from http://www.wsl.ch/info/mitarbeitende/buetler/publications/InFocus-Integrate-chapterHabitat_trees-final.pdf

The Cavity Conservation Initiative (2016). The value of dead trees. Retrieved from http://cavityconservation.com/value-of-dead-trees/

French, B. (2015). Features of habitat trees. http://www.arboriculture.international/environmental-1#environmental

Harper, C. Improving your backyard wildlife habitat. Agricultural Extension Service, the University of Tennessee PB1633I. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/Sotirakou964/tn-improving-your-backyard-wildlife-habitat

National Wildlife Federation. (1997). Turning deadwood into homes for wildlife. Retrieved from https://www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/National-Wildlife/Gardening/Archives/1998/Turning-Deadwood-into-Lively-Homes-for-Wildlife.aspx

Torsello, M. & McLellan, T. (2004). There’s life in hazard trees. Retrieved from http://na.fs.fed.us/spfo/pubs/uf/wl_haztrees/haztrees.htm

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. (2011). Snags—the wildlife tree. Retrieved from http://wdfw.wa.gov/living/snags/snags.pdf

Writter, S. (1997). Dead trees and living creatures: the snag ecology of Idaho. Idaho Wildlife (Vol. 17 No. 4). Retrieved from https://fishandgame.idaho.gov/public/wildlife/nongame/leafletSnag.pdf