Wildlife Connections: Neotropical Birds

By Josie Miller

Before European American settlement, much of the eastern United States, including Kentucky, was widely forested. Today, due to urban, industrial, and agricultural expansion, much of the remaining forest has been removed or fragmented. These remnant forests have long provided habitat, including food and nesting opportunities for both resident and migratory birds.

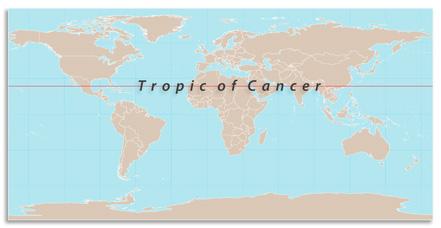

Neotropical Migratory Birds

Neotropical migratory birds are those bird species whose members breed in the United States and Canada and winter in Central or South America, or the Caribbean. The more official dividing line is the Tropic of Cancer which passes through central Mexico. This migration provides greater habitat resources and breeding success due to a decrease in competition from other species. These birds may spend from a few weeks to four months in one-way migration between their breeding and wintering grounds. Neotropical migrants that may be observed in Kentucky include the blue-gray gnatcatcher, eastern kingbird, hooded warbler, indigo bunting, purple martin, red-eyed vireo, scarlet and summer tanagers, and wood thrush.

Feeding the Fall Migration

Scientists have long-studied the destinations of this migration, both the breeding and wintering sites, and note loss of habitat due to development and destruction. Today, stopover ecologists, who study the habitat of neotropical migrants at points throughout the migration, acknowledge that habitat along the migration routes is also compromised. These stopover sites are extremely important to migrant birds who may be flying hundreds or thousands of miles to their destinations. In the spring, birds eat an abundance of insects, and in so doing provide natural pest control for plants and the humans that enjoy them. Doug Tallamy writes in The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, that a single clutch of chickadee fledglings consumes approximately six- to ten-thousand caterpillars. During fall migration, birds seek high-fat berries and other tree and shrub fruits to fuel their massive flights. In Birdscaping in the Midwest: A Guide to Gardening with Native Plants to Attract Birds, author Mariette Nowac states, "the species known to have fruits high in fat include most dogwoods, Spicebush and Sassafras," and the Cornell Lab Citizen Science Blog additionally includes viburnum species in this list. Interestingly, although plants in spring tend to flower and fruit earlier in southern states, and later in northern states, the process is reversed in the fall, with fruits ripening in the north as birds are preparing for their migration, and successively ripening southward as birds progress on their journey. Native plants, which have coevolved with neotropical migratory birds, provide the right food at the right time.

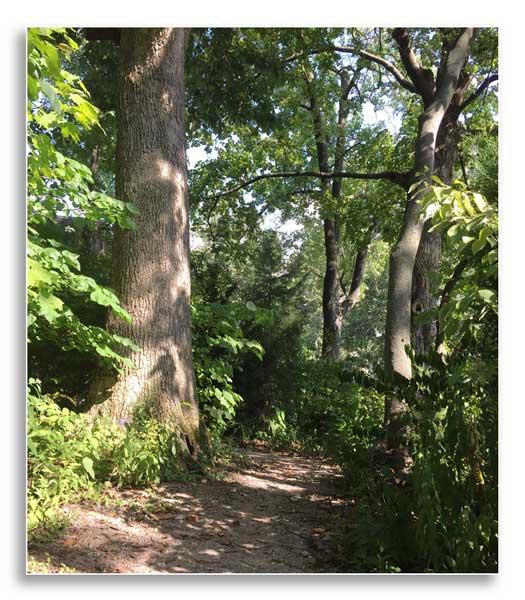

Woodland Reestablishment

Although contiguous forests are decreasing along the migration routes of neotropical birds, small fragments of woodland along the way can and do help. Both individuals and businesses can contribute by creating and maintaining small and large woodlands on their property and throughout their neighborhoods. Individuals may focus on one area of their yard, their entire property, or advocate for connecting woodlands throughout their neighborhood. Businesses can beautify their property and contribute to cleaner air by maintaining small or large woodlands around their buildings. Agricultural lands may be enhanced by maintaining woodland habitat that supports the birds which act as a natural insecticide for crops. Parks, churches, and schools, which often possess ample mowed land, can provide more comfortable environments to visitors, students, and employees by growing woodland gardens throughout their property. In addition to these human benefits, maintaining even small woodlands contributes to the ecological diversity of the region and supports migratory birds.

Migration Stations

By growing a woodland garden planted with a diversity of trees and shrubs, a person can both provide habitat for resident birds, and create a migration station; a refueling station for neotropical migratory birds. When creating a woodland garden, it is best to observe regional remnant forests for guidance and inspiration. Nature preserves and other undeveloped lands support plants that have evolved and are accustomed to growing in the particular soils and climate of the region. Look for areas that are similar to the conditions on your own site, particularly if it is extremely wet or dry, and pay particular attention to the trees and shrubs that grow there. Be aware that some non-native horticultural shrubs and trees have escaped from gardens where they were once planted, and now invade remaining natural areas. A few of the invasive species in our area include bush honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.), Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), and privet (Ligustrum spp.). Although these plants produce fruit that some birds will eat, it does not provide the nutrition that birds require during migration. If you discover such plants on your own property, they should be removed and replaced with native alternatives.

The design of a woodland garden should mimic that of a forest. Small gardens might include one large canopy tree, such as an oak (Quercus spp.), hickory (Carya spp.), maple (Acer spp.) or hackberry (Celtis spp.), or a smaller tree such as a persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) or sassafras (Sassafras albidum). Understory trees could include alternate-leaf dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), hawthorn (Crataegus spp.), and pawpaw (Asimina triloba). Surrounding shrubs might include spicebush (Lindera benzoin), rough-leaf dogwood (Cornus drummondii), and viburnum (Viburnum spp.). Herbaceous perennials provide additional seed, nectar, and shelter. These are just a few of the many possible plants that could be added to a woodland migration station. By growing a diversity of locally native plants, you can enjoy a hospitable atmosphere that will fuel the flights of neotropical migrants.

Photography

- Tropic of Cancer world map (Wikipedia, CC)

- Scarlet tanager; migrates 600 - 4,350 miles from its breeding site in southeastern Canada and the eastern United States to its wintering grounds in northwestern South America (Flickr, orchidgalore, CC)

- (Left) Berries of the rough-leaf dogwood (Cornus drummondii); (Right) Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) berries ripening in the last weeks of August - both create dining opportunities for birds at the University of Kentucky Arboretum (J. Miller)

- Mathew's Garden at the University of Kentucky, home to over 250 species of plants (J. Miller)

- Nestled ina woodland garden, the Kentucky Native Cafe creates a welcoming atmosphere for birds and patrons (J. Miller)

About the Author

Josie Miller is the Stewardship Director at Floracliff Nature Sanctuary, a 287-acre forest and ecological preserve in the palisades region of the Kentucky River in southern Fayette County, Kentucky.