Economic Botany and Cultural History: Northern red oak

By Rob Paratley

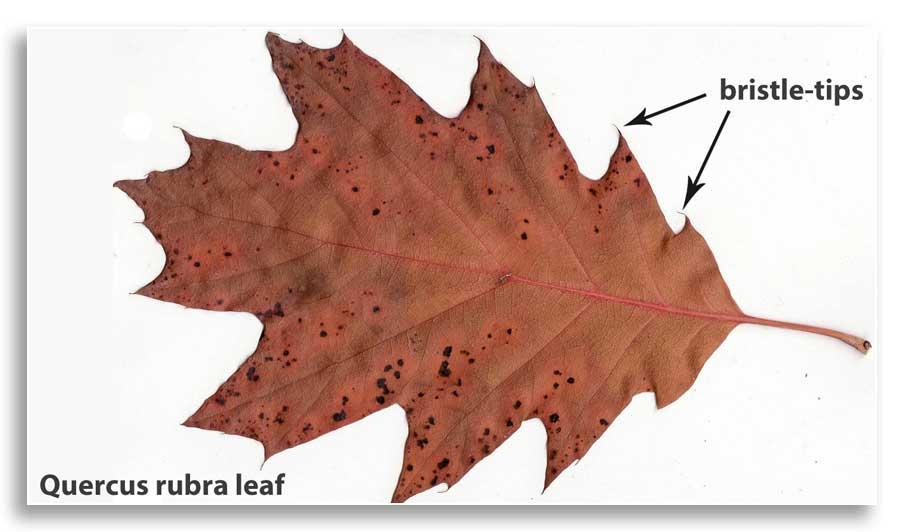

Northern red oak, Quercus rubra, is one of the two most important oak species in the regional flora. Northern red oak is one of the red or black oaks, distinguished from the white oaks by bristle-tipped leaves, and acorns that take two years to mature, as well as some anatomical differences in the wood. In technical botanical sources, you will see Quercus rubra L., meaning that the valid name was first given by Carl Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum in 1753. As you look in different manuals you may run across the name Quercus borealis F. Michx. for northern red oak. This name was given to it by Francois Michaux, the son of the great French botanist-explorer Andre Michaux, published in his North American Sylva (1810- 1813). The earlier Linnaean name is regarded as the correct one.

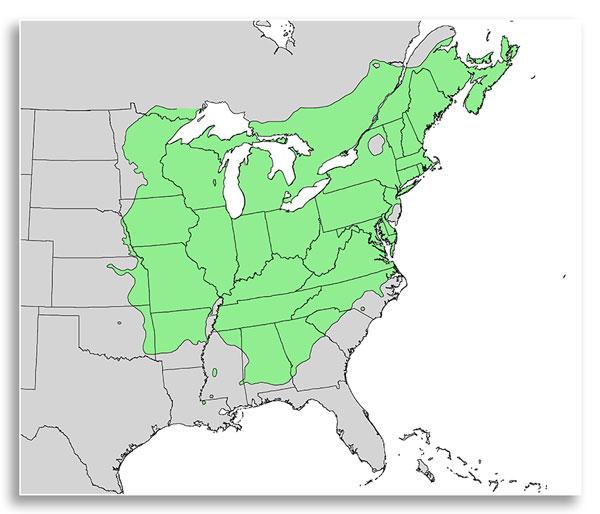

As befitting its common name, it is the northernmost ranging oak in eastern North America, found at lower elevations in the Laurentian northern hardwood forests of the Canadian maritime of Quebec as well as the forests of coastal Maine. Northern red oak is found at lower elevations throughout most of New England and New York State. In these northern forests, northern red oak is found as an occasional tree in a forest otherwise dominated by sugar maple, beech, red maple, and perhaps the conifers eastern white pine and/or eastern hemlock. Many northern red oak populations in these northern states are classified as a named variety, var. ambigua with deeper acorn cups.

In the Central hardwoods of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, northern red oak is commonly found in mixed oak stands with white and black oak. Here it may reach great height (there are documented northern red oaks topping 150 feet.) Further north toward Lake Michigan, it associates with eastern white pine and aspen.

In the South, northern red oak is common component of Piedmont forests, but barely extends into the Coastal Plain of the Gulf States, relegated to sheltered sites with moist, productive soil. In the high heat of the southern summer, its atypically shallow root system (for an oak) renders it at a competitive disadvantage in the dry spells of the southern summer and fall.

On the other hand, this shallow root system renders the tree quite competitive on rocky ridges and bluffs in many parts of the Appalachian chain. In the southern Appalachians, northern red oak is a member of rich cove hardwood forests, attaining great height. It is found higher in the southern mountains than any of its oak cousins, commonly seen in northern hardwood stands above 4,000 feet and recorded as high as 5,500 feet. These high elevation stands have oaks that are a far cry from the majestic specimens of the rich coves below. Here in the higher mountains, northern red oak is a wind-blown gnarly tree not much more than twenty feet tall. Along the rocky, windy flat ridges in Ridge and Valley province in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and lower New York State, northern red oak may grow in single-species stands or associate with chestnut oak or the shrubby bear oak.

Here in Kentucky, northern red oak is found throughout the state on a variety of sites and soil types. It is most competitive and reaches best growth on rich loam soils which are well-watered but also well-drained. It is not at all a wetland tree and tolerates flooding poorly. On these sites, a variety of trees form lush mixed mesophytic forests. In mature forests in our state, on best sites, northern red oak can exceed 110 feet in height and three feet in diameter. Its growth form is often excellent- a straight bole with first branches high above the forest floor. Like other oaks, northern red oak is not tolerant of shade. Although many reference books will classify it as moderately tolerant, this is deceptive. Seedlings will establish here and there on the forest floor, and they can persist for years, but, without disturbance, they eventually succumb. A sapling even ten feet tall would be most unusual in the shade of the forest. So northern red oak can exploit moderate-sized light gaps caused by treefall (while many oaks need a greater thinning of the canopy by natural causes or forest management). Its growth rate on productive sites is quite good, reportedly one of the fastest growing oaks.

Northern red oak is a valuable timber tree, certainly the most valuable of the red oaks. It is valued both for its generally excellent growth form and for the strength, durability, and attractive grain of the wood. Like all oaks, it is ring-porous so the earlywood vessels are conspicuous and result in a coarse grain. The heartwood is a light pink, and is quite permeable (especially compared with white oak). It takes stain and polish well, making it a desirable high-end wood, used for fine furniture, cabinetry, flooring, molding, and cooperage. Lower-end uses include construction, mine props, and railroad ties. The wood burns hot and makes good fuelwood. Because it is prone to insect attack and decay, the wood is not favored for exterior work in the building trade.

Like all oaks, northern red oak flowers in spring before leaf-out. It produces male flowers in stringy catkins and female flowers tucked away in tiny, hard-to-see cymes. Pollen is shed to the wind, and, if fertilization is successful, acorns are produced. Look for the acorns not on this year’s twig growth, but last year’s because of their two-year maturation. Oak acorns of course are important wildlife food and exhibit much higher production, masting, every few years. Northern red oak typically masts every two to five years. Some individual trees are consistently better acorn producers than others. Most acorns are consumed by a variety of animals, from bears and raccoons to rodents, game birds to jays. In almost all situations, though, the northern red oaks we see in the second-growth forests of our region did not originate from acorns, but rather from sprouts. This tree is a good sprouter when injured or cut, better than some oaks (like white) and perhaps not as good as others (chestnut oak).

Like most oaks, northern red oak forms viable hybrids, in this case with other red oaks. In our region, hybrids typically form with black oak, pin oak and Shumard oak These hybrids confuse tree identifiers, but in my experience, hybrids aren’t that common. In other regions, the other parent will vary. In the South, for instance, northern red oak – willow oak or blackjack oak hybrids are seen.

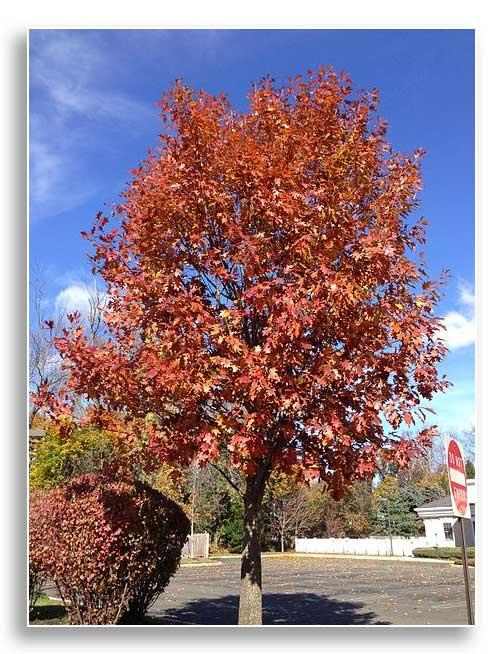

Northern red oak very valuable as an ornamental street and park tree. Easier to transplant than most other oaks (the shallower root system), it does reasonably well in urban conditions. Crown form is rounded and spreading; fall color varies with the cultivar- sometimes red but often nothing special. The tree is hardy in the north to Zone 4 (or colder in special cases). As a cultivated tree, it tolerates soils from acidic to alkaline, and performs well on all but very wet or very dry soils. The tree is reasonably disease and insect resistant, although the gypsy moth can do extensive damage in the northeast and oak-wilt disease has done much damage to the species in the upper Midwest.

Photography

- Red oak leaf - modified with added labels (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Red oak range map (USGS Public Domain)

- Red oak acorns - modified with crop (Wikimedia commonc, CC)

- Red oak street tree (CC-ASA-4.0)

About the Author

Rob Paratley is an Agriculture Research Specialist in the University of Kentucky Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. Rob has taught several courses at the University of Kentucky including Taxonomy of Vascular Plants, Economic Botany, and is the Curator of the UK Herbarium. Email Rob at rparatl@uky.edu.